I sat in on a meeting recently where a large, established CPG client reviewed their competitive market data. After looking at several graphs and pie charts comparing them to the other top three competitors (while their team explained and defended basis points increases and decreases in market share), I took notice of one pie chart in particular.

“What’s that?” I asked, pointing to the grey slice in the pie chart marked “other.” It appeared to be growing over time on Amazon.

“Very small competitors. We don’t need to worry about those ones,” he said. Then he laughed, looking around the room at his colleagues. “Those are the ankle-biters.”

Ankle biters? I wonder if PowerBar thought ONE bar was an ankle-biter. Or if Skippy was worried about PB Fit powdered peanut butter disrupting their “category”. Or if Kimberly Clark had thought Dude Wipes would revolutionize the ancient toilet paper business.

In looking through the list of brands, I could understand why the client wasn’t interested in them. They were a list of brands that weren’t available at major retailers.

However, this list of “ankle-biter” brands were at the top of Amazon search. And search presence is a leading indicator of success online.

CPGs should take note of these small competitors, and here’s why.

1. Competitors online are usually vastly different players than in brick and mortar.

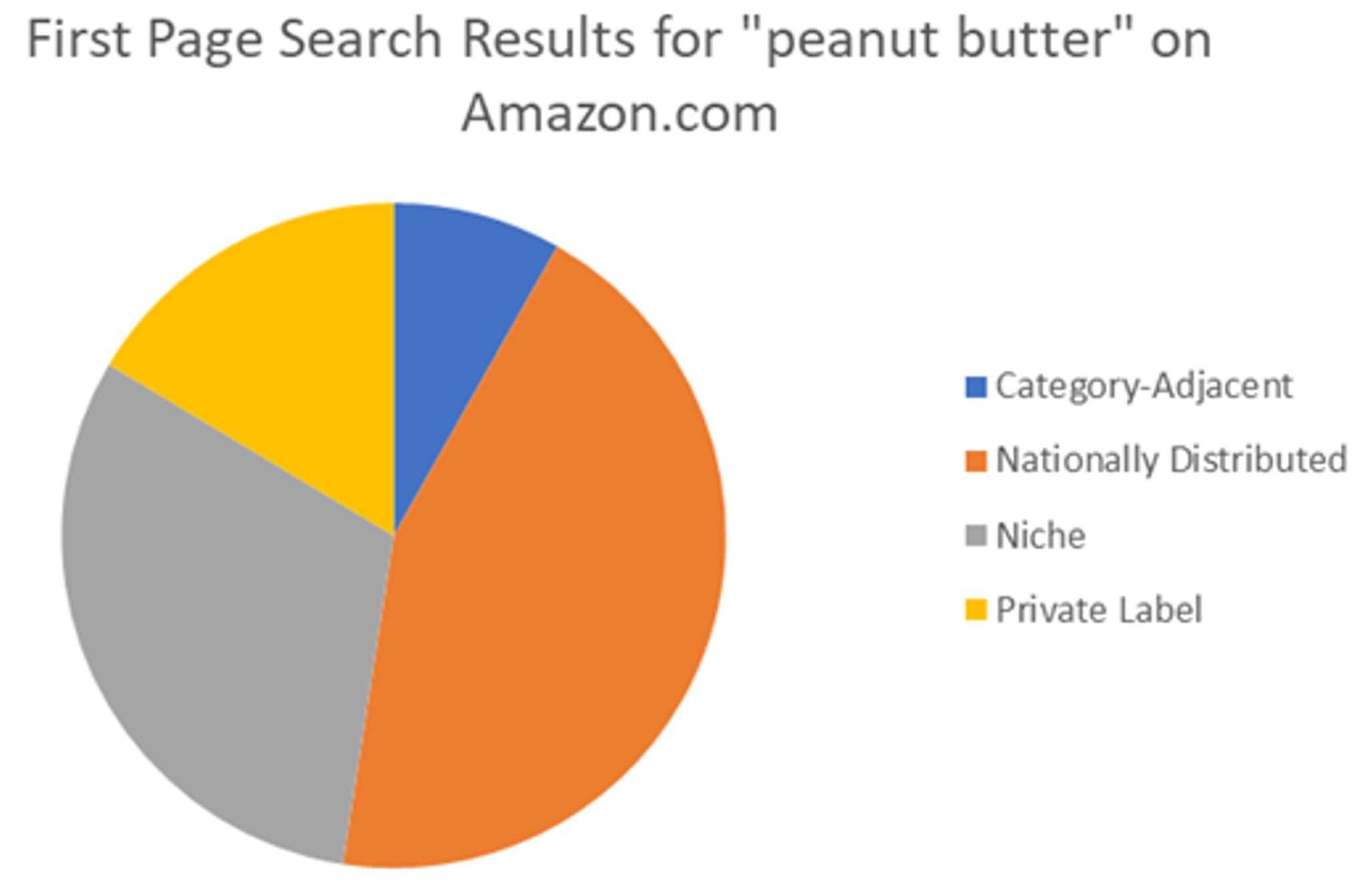

And, scarier. For example, look at the below chart of Share of Search for the search term “peanut butter” on Amazon (a top 1,000 search term). More than half of the first page of search results are either local or niche brands, category-adjacent, or Amazon private label.

Amazon’s assortment and search strategy heavily favor more profitable, niche brands. And customers heavily favor Amazon’s search results in their purchase behavior.

Based on the pie chart below, these don’t look like “ankle-biters” to me.

My guess, however, is that Skippy isn’t tracking most of these brands in their market share data. Instead, they are likely focused on their top brick and mortar competitors.

2. Marketplace-native brands can quickly grow to nationally distributed brands if not treated as “real” competitors by large CPGs.

I continue to see clients underestimate the potential power and customer following of these upstart brands. Marketplace-native brands (low threats) can quickly become large, nationally distributed brands (big threats). Here are a few examples:

Anker Innovations came out of nowhere and eventually dominated the cell phone accessories business, more accessories than Samsung and Apple themselves. I mentioned Dude Wipes above (and here’s a great podcast where I interview their founder here). A toilet paper alternative, they started off just on Amazon. Now they are in most major retailers and have proved themselves a major disruptor of the toilet paper industry, stealing share from Kimberly Clark.

Nuun used to own the powdered electrolyte market, but not anymore – Liquid IV is now the top search result on Amazon for electrolyte drinks. Bai beverages was another marketplace-native brand. They had a meteoric rise to stardom, including securing investors such as Justin Timberlake. Keurig Dr. Pepper ultimately acquired them…an expensive outcome for them.

3. Investors believe in the power of marketplace-native brands, even if traditional CPGs don’t.

We can see this through the enormous sums of money being funneled to FBA aggregators such as Thrasio, Perch, and others.

Small brands on Amazon no longer have to be small. These days they can get scooped up by aggregators with aggressive advertising budgets and sophisticated technology and become rather frightful competition quickly.

Takeaways

Don’t underestimate the power of marketplace-native brands. Make sure your organization is looking at metrics to help identify these competitors early. Namely, in search results, if you can.

By the time they hit your market share sales chart, it will be too late—and very expensive—to compete with them.